9 April – 24 May 2014

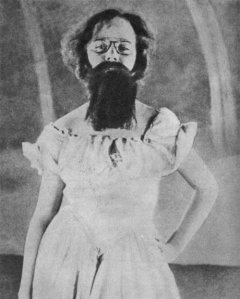

William Kentridge is now included within the “canon” of contemporary political artists. Born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1955 he is one of the relatively few colonials to reach such a level of success in circles which remain dominated by Western European and United States’ artists. Kentridge’s identity as a white Jewish South African anti-apartheid supporter has played a central part in the interpretation and reception of his work.

Kentridge has had a long association with Australia, largely established through the support of Ann and Bill Gregory at the Annandale Galleries, who began showing him in 1995 when he was virtually an international unknown. His eighth solo exhibition there ran to coincide with the 2014 Sydney Biennale although it was not part of the official program. This small gallery in Sydney’s inner west remains associated with him even though his international profile is now so high.

Kentridge’s work is both overwhelming and deeply puzzling. He is best known for prints, drawings and the animated films he constructs with them. Sheet after sheet of paper is covered with charcoal or graphite drawings, each sheet being photographed and then partially erased and changed, the final sets being made into a film using a kind of primitive animation technique. He is also a sculptor, designer and interpreter of opera.

There is nothing easy in Kentridge’s work. The viewer needs an instinctive gut reaction, and some knowledge of South African history and politics, to grasp the intent behind his sparse, rough and expressive works. He began making prints and drawings in the 1970s with a series of monotypes and small format etchings showing domestic scenes and localities. Later he made charcoal and pastel works focusing on the blasted dystopian urban landscape.

Between 1989 and 2003 he made a series of nine short animated films, “Nine Drawings for Projection”. This elaborate project established him as a practitioner of a new kind of visual art. His most recent work, of which the 2014 Annandale Galleries show is an example, is linked to the use of text, word and image in animated films alongside startling graphic images printed on old texts such as the pages of the Oxford English dictionary.

The 2014 show is called “SO”, just one more element of the puzzle of what is going on in Kentridge’s imagination these days. It fills both floors of the gallery, offering mainly prints and some sculptural pieces, along with a series of three animated films. The latter, along with some associated graphic prints which make up the components of the films, are shown downstairs, irritatingly close to the front desk and subject to all the noise of a small gallery space as people enter and leave. This is a great disappointment as the viewing of these films is in my view the key to understanding the exhibition as a whole.

The prints take a lot of looking at and demand intense focus. “The Hope in the Charcoal Cloud” offers a series of drawings of the artist printed on the pages of an old dictionary, as he steps up and down on a low stool, interspersed with the printed word “SO”, a single red-coloured sheet, and a sequence of four images which look like the earth or the moon, prefaced with a printed statement “TIME IN THE GREY PAGES”.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that this represents a statement of the artist’s own sense of his (and our?) existence. He hopes every day to achieve success in the charcoal cloud which he creates as he works diligently on his sheets of paper, creating graphic images of himself. He repeats his actions, going up and down that low stool over and over again. Having got onto it the first time, he says “SO”, which could mean “so what?” or something completely different. Off he goes, doing it again. He runs into the red barrier, which might be his own blood, but off he goes again, and finally realizes that he is facing his mortality as the grey pages he is creating pass by over and again. The earth, maybe a dark moon, and a globe on a stand complete the sense of Time and its passing.

But this is just one interpretation and there is nothing in the work to encourage us to think that any one might be better than any other. It is almost like encountering a Rorscharch test. One wonders if the same sequence was shown to twenty others, how many would come up with a similar interpretation? And to what extent is this, or any other, interpretation dependent on the written texts that bookend the images? It is a kind of narrative art which refuses to disclose the narrative.

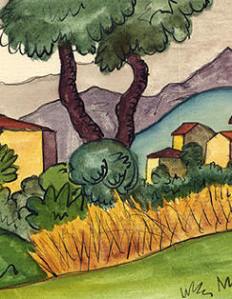

Kentridge has long been fascinated by trees, particularly the species indigenous to South Africa. This is something Australian viewers might find particularly compelling. Many of his recent images, including those at the Annandale show, involve a combination of prints forming images of large trees. These were obviously popular with the audience as most were sold.

Universal Archive: Big Tree 2012 linocut

Davidkrutprojects.com/artists/William-kentridge-universal-archive

The sense of intrigue in the work, evident in the Charcoal Cloud discussed above, becomes even more compelling in the animated films. These works invite the viewer to consider them as a philosophical event. In the midst of striking images and forms, texts appear which seem to suggest a platform or conceptual grid beneath the surfaces. For example, in the midst of an animated film certain messages suddenly appear and disappear: ANYTHING TO SAY? With the question mark hand-drawn clumsily.

Universal archive: Ref 52, 2012.

Or, in the midst of a series of images printed on the old pages of The Universal Technological Dictionary, a lively black bird carries a sign: WHICHEVER PAGE YOU OPEN THERE YOU ARE.

RETURN TO THAT PARTICULAR MOMENT, 2013

INDIAN INK ON UNIVERSAL TECHNOLOGICAL DICTIONARY: OR, FAMILIAR EXPLANATION OF THE TERMS USED IN ALL ARTS AND SCIENCES: CONTAINING DEFINITIONS DRAWN FROM THE ORIGINAL WRITERS, AND ILLUSTRATED BY PLATES, DIAGRAMS, CUTS, &C, VOLUME 1 AND 2 BY G. CRAGG, 1823

40 1/8 X 39 3/4 IN. (102 X 101 CM)

His use of three old book texts and their pages in the 2014 film work also invites philosophical discussion. The pages of the Oxford English Dictionary provide one support. The second (above) is the Universal Technological Dictionary; and the final one is Richard Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. Do the images and interspersed texts relate to anything specific in these works? Is the film printed on Burton’s old work, one of the first discussions of depression in English writing, to be interpreted as a meditation on the meaning of sadness and sorrow, or even as the product of a period of depressive illness? There is nothing to tell us and no way to know, and it is especially frustrating with the films as there is no way to slow them down and “read” them through a narrative grammar, even though one is implied by the very form of the work.

Kentridge’s use of animated film seems to be accepted by most critics and commentators as just another element in his diverse art practice. Arguably, though, it is the key medium through which he has approached the political underpinnings of his work. Like most white South Africans he has been forced to confront the issue of white guilt. In the 1990s he made a series of nine remarkable semi-autobiographical films, including Felix in Exile (1994) and History of the Main Complaint (1996). This series is read by Erickson (2011) as being shaped by the confrontation of two strong needs, to acknowledge white guilt and to find a means of redemption. In these films the key structural elements of gender and race undergo shifting patterns. He creates two characters, both of which can be understood as elements of himself. Soho Eckstein represents the dominant white male, Felix Teitlebaum the artistic and sensitive male. The only real female characters are both black females, a woman called Nandi and a black nanny. Hence the fundamental model for white-black exchange lies in transactions between a white male and a black female. In Tide Table (2003), Kentridge goes into his past to retrieve the memory of his own black nanny seeking for a tentative act of blessing through gestures of recognition. Erickson’s fascinating analysis unpacks clearly what is going on in this series of films which traverse themes of guilt and redemption in surprising ways. Today, though, this series of films seems to have virtually disappeared from critical comment on Kentridge. It is as if the in-depth exploration of a deeply disquieting personal memory, infused with a horrifying history and politics, is many steps too far for our contemporary awareness. That era, and those questions, seem now to have been repressed. Perhaps, for Kentridge, he has gone through them and has nothing more to say about it. His recent animations reflect his earlier pre-occupations only in the most minor register.

Viewing his three animations in the 2014 show, one is struck by their apparent incoherence. Boer (2013) offers a highly nuanced account of what is going on in these and other of his films, from the viewpoint of a history of film animation. She shows that Kentridge uses many familiar stylistic features and techniques of this medium, which Krauss has referred to as “stone-age film-making” (Krauss 2010: xiv et seq). Krauss concludes that Kentridge’s work is even more “primitive” than the first forms of Disney cartoons and the thaumatrope. Boer describes the elements of commonality between Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection and the early black-and-white Disney cartoons (Boer 2013:1148). Without an extended commentary on her very subtle and ingenious essay, it is helpful to note that the intersection between art, violence and technology is exactly the intersection where Walter Benjamin, in The Work of Art (1935) situated Mickey Mouse.[1] A full comprehension of the import of Boer’s analysis makes the reception of Kentridge’s film work even more problematic than it would seem at first glance, which is the only glance which most viewers of his work will ever have, that is, a quick view of some flickering scenes in a gallery somewhere. Following a careful analysis of specific scenes in some of his films (eg Weighing … and Wanting, 1998 and Tide Table (2003) Boer suggests that Kentridge is drawing attention to the artificiality of reconstruction and questioning the idea that reconciliation, both personally and in the larger South African context, can paper over cracks seamlessly even while leaving them intact. The technology of animation allows for a visual demonstration of this idea, so that “the viewer is called upon to view these shots with suspicion, exactly because they seem to erase the consequences of the oft-violent events that took place on-screen during the filming” (Boer 2013:1167).[2]

To what extent can the traces of this political past retain an equivalent vitality today, or has his concern with the chaos of those years transmuted into a more indirect autobiographical direction in his later work? Terry Smith (2011:48) raises the question of whether today “we”, and the artist, can “relax a little” and “enjoy the fruits of his protean creativity”. His major recent show (2010) offered a comprehensive survey of his career and toured many of the major museums and galleries around the world, including a show at MoMA in New York. This show integrated his graphic and other works with a production of Shostakovich’s opera The Nose at the Metropolitan Opera. Kentridge studied mime and theatre in Paris in the early 1980s, and the show Five Themes brought together a kaleidoscope of imagery in sixteen acts, referencing the constructivist scenarios of the early twentieth century. This work used no direct elements from the political context of South Africa, although Smith argues that it retains a form of activist uncertainty and a sense of political art, which, in his own words, is “an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings” (Kentridge, quoted in Christov-Bakargiev 1998: 136).

Nevertheless, in his 2014 show a major piece consists of a 42-panel gridded picture of a tree, called Remembering the Treason Trial (2013). It refers to the 1956 trial of Nelson Mandela, in which he was successfully defended by Kentridge’s father Sydney. As McDonald comments “the work is covered in sentences, some portentous … others more mundane” (2014). McDonald remarks that in this work personal recollection and historical memory have been blended “drawing the private and public realms into one all-encompassing image”. Kentridge’s use of text and writing is particularly striking in this piece, as if he is trying to blend his graphic art with a form of literary memoir.

The wealth and depth of Kentridge’s work makes it difficult to evaluate in terms of conventional forms of contemporary art. In combining drawing, design, graphics, print-making, sculpture and animated film, and performance art of a kind if we include his opera-based work, it is as if he offers too much and not enough at once. The show at Annandale Galleries offers a small taste of the oeuvre, familiar in form to previous recent work, but if the viewer is unfamiliar with that work it seems to make very little “sense”. Should contemporary art make “sense”? In the case of Kentridge, it feels as if he insists on sense-making with the many texts and ambiguous written statements, while defying any attempt to put the narrative together. That is, perhaps, his key message: it is impossible to get past uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings. Or, as Boer (2013) concludes in her essay, Kentridge is using his various forms of paper as a means of wrapping up South African social and political issues without attempting to resolve them. (2013: 1168).

References:

Benjamin, Walter. 2008. The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility: second version. Trans. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn. In The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media. Ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. (See Endnote 1).

Boer, Nienke. 2013. Taking a joke seriously: Mickey Mouse and William Kentridge. MLN, Vol 128, 5 1146-1169.

Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn. 1998. William Kentridge. Brussels: Societe du Palais des Beaux-Arts/Vereniging voor Tenstoonstellingen van net Palais voor Schone Kunsten.

Hansen, Miriam. 1993. Of mice and ducks: Benjamin and Adorno on Disney. The South Atlantic Quarterly 92.1: 27-61.

Krauss, Rosalind. 2010. Perpetual Inventory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McDonald, John. 2014. William Kentridge: SO. Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 10 May 2014, accessed 14/6/14].<http://johnmcdonald.net.au/2014/richard-mosse-william-kentridge/#sthash.XmH48Y9P.dpuf >

Smith, Roberta. 2010. Anger and Angst. New York Times, 26 February 2010.

NOTES

[1] Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (which is more accurately known as “The Work of Art it the Age of its Technological Reproducibility”) discussed the difference between early Disney cartoons as a form of mass entertainment and the role of Nazi spectacle. This section of his essay was omitted from the well-known English version of the essay published in Illuminations (1969), a translation of the 1955 German version edited by Adorno and Podszus but included in the new edition of 2008 devoted specifically to his writings on media. For more in this, see Hansen 1993).

[2] Boer’s long and elaborated argument suggests that Kentridge has chosen the medium of animation as a way of engaging in “developed play” since the rules of animation require the operation of visual perception in its relation to the unconscious. The viewer has to be “trained” to read the arbitrary rules of animation, and Kentridge uses these rules in order to demonstrate their limits.

iewer to respond? At first the viewer seems invited to identify with his pain. But soon one begins to ask, is it really such a terrible tragedy that a once-wealthy man lost his dream home? Isn’t his anguish and distress absurdly OTT? Why should people devote such passion to the building of “Their House”? What made it possible for him in the first place to acquire the capital which would allow him to engage in such a project? The vast empty premises of the Landsbankinn – one of the first banks to collapse – seems somehow appropriate to the icy wastes beyond.

iewer to respond? At first the viewer seems invited to identify with his pain. But soon one begins to ask, is it really such a terrible tragedy that a once-wealthy man lost his dream home? Isn’t his anguish and distress absurdly OTT? Why should people devote such passion to the building of “Their House”? What made it possible for him in the first place to acquire the capital which would allow him to engage in such a project? The vast empty premises of the Landsbankinn – one of the first banks to collapse – seems somehow appropriate to the icy wastes beyond. ing for art. At auctions the investors have advisers and agents on the phone, pushing prices up to astronomical levels supported by the insanity of the global economy. They can bid for and buy art from anywhere in the world, and they do: they come from Russia, from China, from Brazil. We meet the Auctioneer, in this case playing himself, Simon de Pury. He becomes anxious and excited before each major auction, eating an apple for luck. One “painting” which consisted of a written text on a wall sold for 1.2 million, a super-modest price compared with the 42 million paid for a Roy Lichtenstein in 2011. Art and antiques became part of the equipage of the wealthy class in the post-crisis mistrust of esoteric financial instruments. The Global Financial Crisis helped the art market beyond anybody’s expectations. During the GFC only 50% of items offered for sale were sold: now it is nearer 90%, springing back after the huge Christie’s auction in Paris in March 2009. Chinese star Maggie Cheung, who appears in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves, plays the role of an eager interviewer. In reality, the two never were together and each segment was filmed separately and intercut artfully.

ing for art. At auctions the investors have advisers and agents on the phone, pushing prices up to astronomical levels supported by the insanity of the global economy. They can bid for and buy art from anywhere in the world, and they do: they come from Russia, from China, from Brazil. We meet the Auctioneer, in this case playing himself, Simon de Pury. He becomes anxious and excited before each major auction, eating an apple for luck. One “painting” which consisted of a written text on a wall sold for 1.2 million, a super-modest price compared with the 42 million paid for a Roy Lichtenstein in 2011. Art and antiques became part of the equipage of the wealthy class in the post-crisis mistrust of esoteric financial instruments. The Global Financial Crisis helped the art market beyond anybody’s expectations. During the GFC only 50% of items offered for sale were sold: now it is nearer 90%, springing back after the huge Christie’s auction in Paris in March 2009. Chinese star Maggie Cheung, who appears in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves, plays the role of an eager interviewer. In reality, the two never were together and each segment was filmed separately and intercut artfully.