Gerhard Richter is the towering figure of contemporary European art. You’d never know it in Australia though. Apart from the brave retrospective at the GOMA in Brisbane (October 2017-February 2018) Richter’s art and reputation barely registers here. One can speculate about the reasons: his early art was weird (he painted full-scale black and white oils which were blurry copies of old photographs), his landscapes were almost abstracts and then when he started painting abstracts they looked like landscapes) but quite apart from the art, he has never comported himself like a suitably glamorous and dramatic/exotic figure and of course there is the contemporary sticking point, he is an old white male and a German at that.

Richter was born in 1932 and spent his boyhood in obscure Lower Silesia, now Bogatynia, Poland, and in the Lusitian countryside. The family moved to Dresden where his father, a teacher, struggled under the emerging Nazi education system. He was forced finally to join the Nazi party. Gerhard aged 10 was conscripted into the Hitler Youth but was too young to be an official member. Somehow the worst effects of the war passed the family by, and Gerhard was able to study at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, where his first application was rejected because his work was too “bourgeois”. Now he was living under the DDR, but managed to escape to the West two months before the building of the Berlin wall.

So, an early life under the shadow of the Nazis and the Commies, then freedom in the West and a dazzlingly successful career in art. So has gone the accepted story. Richter has been extremely protective of his privacy and although he has given many interviews and written his own books (wonderfully stimulating books) he has never strutted the stage as the kind of glamour boy which the art world so adores. He hasn’t been a drug addict or murdered anybody and he has nurtured his reputation by judicious management and with a quiet sincerity which is so against the grain these days.

Perhaps this reticence has aided his growing reputation. As the international art scene became big business in the new millennium a strange phenomenon occurred: the older and quieter Richter became, the greater and greater were the sums being paid for his work. Richter has become beyond collectible. In 2012 one of his Abstraktes Bilde set an auction record for a living artist at $34 million US. In 2013 his 1968 piece, Domplatz, Mailand sold for $37.1 million and in 2015 another Abstraktes Bild sold for $44.52 million.

Richter himself has watched this bizarre development with no little distress. These staggering prices do not go to him, of course, but to whoever had the foresight to buy his work earlier. He has described the situation as “absurd” and “daft” in 2011.

As this huge and unstoppable process continues, he has been saying less and less about it.

But now everything has changed. In this age of self-curation and self-revelation, everyone has to have a narrative and they have to share it with the world and if it contains a lot of bad stuff so much the better. For some unknown reason Richter permitted famous German film director and Oscar winner Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck (The Lives of Others, 2006) into his life and thoughts. For weeks they met and Donnersmarck recorded candid conversations with Richter about his life, on the understanding that the resulting screenplay would be “fictionalized”. The film, titled in German Werk Ohne Autor (Work Without Author) was released in Germany in 2017 and while its central character is not called Gerhard Richter and none of his actual paintings are shown (one of his assistants was hired to paint pictures like them for the movie) everyone is referring to it as the biopic about Richter. Now it is about to be released in the US, although at this date (January 2019) there has been no release planned for the UK or Australia.

What did he imagine would happen? Perhaps it speaks to the naivety of an older person about the operations of the new technologies of knowing (of knowing everything about everybody all the time whether they like it or not) or perhaps he trusted Donnersmarck as a fellow-artist. But the resulting film has resulted in a scandal of a horrible kind. No, it’s not allegations of sexual impropriety or dirty secrets, it’s somehow worse than that.

It turns out that between 1937 and 1967, while Richter was consolidating his art practice and developing his early career in East Germany he was benefiting from the support and patronage of his first wife’s father, a former Nazi officer who worked in the euthanasia program. One of Richter’s most famous early monochrome blurred photo-paintings “Aunt Marianne” is based on an image of his aunt, who was herself captured, sterilized and executed as part of the euthanasia program.

Richter is very angry and upset about these revelations. He rightly judges that the fictionalization will become the truth. He has repudiated both film and director, although Donnersmarck says he hasn’t even seen the film yet, only the trailer. Never Look Away has been nominated for an Oscar and for the Golden Globes, and will be released in the US shortly, so everyone will be seeing it soon.

Donnersmarck’s film is an act of provocation, both to the art world itself and to the continuing German reluctance, or refusal, to face up to the realities of the twentieth century past. More and more films focusing on this issue have been emerging lately, and this can be seen as just another in the series. By putting this world-famous artist’s story, even in disguise, at the centre of an ethical demand it creates a compelling focus for the kind of coming-to-terms with the past which every Western nation needs to undertake. The role of art in collective self-recognition, and its role in the revelation of trauma under the unfolding of historical events, has never been more compelling. In a way Donnersmarck’s films make the psychoanalytic demand: live in the register of Truth!

Has Richter’s famous privacy been an effort to cover up or disguise his entanglements with German history? If so, why has he made these revelations to a film director famous for his work in disrobing historical disguises? Did he really think such a film would not be “about” him? Or is there some inner compulsion at work, where his own reality is demanding a release? In some ways the whole situation reminds me of what happened when Martin Heidegger’s “Black Notebooks” were published recently. Right-wing critics and philosophical conservatives went through them line by line, trumpeting “See we told you all along he was a Nazi” as if this disproves the validity of his writing and hence the whole of contemporary leftist philosophy.

Is this about to happen to Richter and the “value” of his art? Or will it only make it more valuable?

But there are more profound questions here. Is everybody always responsible for decisions they made in the distant past when everything was different including the meaning of behavior? Was Richter wrong not to denounce his wife’s father? How much did he in reality accept from her family, to what extent is his present success the result of these murky antecedents? Has his whole life been a kind of cover-up? And isn’t everybody’s?

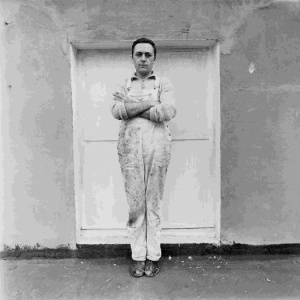

In the poster for the German film (above) we are confronted with a beautiful young man who seems to be hiding behind his own blurry hands. This is the director’s message, perhaps. I haven’t seen the film and I look forward to it. At over three hours long it probably won’t receive a release in Australia but who knows, maybe SBS will get some cojones after the next election and go back to its original mandate.