[Photograph: Annette Hamilton 2012]

Elisabeth Cummings (b. 1934) is not well-known among the general art-going public. She has been devoted to her art practice, mostly painting, for over fifty years. Few of her works appear in any public gallery collections in Australia. Based in Sydney and its bushland outskirts, she has travelled and painted in outback towns and in remote Western and Southern Australia. In 1996 she was given a survey exhibition by the Campbelltown City Bicentennial Art Gallery, but at that time she had only one painting in the collection of the Art Gallery of NSW, while one work in the National Gallery of Australia had been transferred to Artbank. Nothing had changed six years later. Recently her work has been receiving more recognition. Several smaller public collections hold paintings, and she is increasingly sought by avid collectors. She has won a number of prizes, and recognition of her importance as an Australian landscape painter has grown. The 2002 Art Collector Magazine list placed her in the 50 most collectible Australian artists.

In 2012 she received a major survey exhibition at the S. H. Ervin Gallery titled Luminous: The Landscapes of Elisabeth Cummings. One of her largest works, Edge of the Simpson Desert, was a highlight of the show.

Edge of the Simpson Desert, 2011. Oil on canvas, 175 x 301 Private Collection

This is hardly conventional landscape art. It is edgy, figurative only in places, filled with spaces and lines which demand patient scrutiny before the forms reveal themselves. It is something like Slow Food. Hers is a slow art: slow to be painted, and calling for close engagement and patient appreciation from the viewer. She works with the local, and paints where she is. Whether travelling through the remote deserts or sitting on her verandah in her studio at Wedderburn, or inside with the light pouring on the mud-brick walls, her faithful black dog at her feet, Cummings is resolutely there in the moment.

Inside the Studio. Photograph: Annette Hamilton 2012

She has been called The Invisible Woman of Australian Art (Frost 2002). But she doesn’t really care about visibility, or profile, or her “career”. Now in her late seventies, she continues to work and live as she has always done. She paints, and teaches these days in the occasional workshop (see for example Champion 2012). She hates being interviewed especially about her personal life. One journalist from the Sydney Morning Herald insisted on an interview while she was confined to a wheelchair following an operation on her right ankle. He tried to force her to reveal elements of her emotional life, on the grounds that this is “the fundamental raison d’etre of any artist”. She found this an absurd proposition, and managed to be so unpleasant to him that he left with his irrelevant curiosity unsatisfied (personal communication, and see Meacham 2012). Cummings is the last person to want to be a celebrity, although she has many close friends in the art world and always has invitations and events to participate in, if she wants to. But she likes a quiet life, and loves her “bit of bush”, even while mourning the fact that it is being encroached on by the endless march of suburbia.

Sydney Morning Herald art critic John McDonald has been one of the few vocal supporters. In Art Essays, January 21 2012, he pleaded that a new show from the National Gallery of Australia of landscapes to be held at the Royal Academy London should include those artists who are making an outstanding contribution to Australian landscape art today, the foremost of whom is Cummings. He deplores the short-sightedness of Australian public collections.

“While galleries have been queuing up to buy works by a handful of fashionable artists, they have treated landscape painting as if it were a purely historical phenomenon.” (McDonald 2012)

Cummings herself has nothing to say about the “fashionable” contemporary arts. Her positive frame of mind does not dwell on endless comparisons or bother to condemn the fetishization of certain forms of current art-making and the implicit rejection of the unfashionable genres.

An excellent video interview in Wedderburn, with Peter Pinson, puts a frame around many elements of her life and art (Pinson 2012). Her father was an architect (as is her son now) and her family supported her interest in art as a profession – unusual for a woman in those days. She attended the National Art School in Sydney, and won a Travelling Scholarship in 1958 which allowed her to spend time in Europe, staying in a villa with friends near Florence. In 1961 she studied under Oskar Kokoschka, a late German expressionist associated with Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt. Kokoschka established his “School of Seeing” at the Internationale Sommerakademie für Bildende Kunst in Salzburg, thus re-establishing his ties with the Austrian milieu in which he began his career, and Cummings was able to spend time there exploring the highly distinctive, and disturbing, post war European sensibility.

Oskar Kokoschka. Bodegon with Affair and Rabbit. 161 x 118. 1914. www.wikipaintings.org

Cummings is often referred to as “reclusive” (Frost 2002). Her Wedderburn studio is the site of an artists’ community established in the early 1970s. Two of its founders died in 2013, Roy Jackson of cancer in July, John Peart in October, a sudden and wholly unexpected death at the age of only 67. Other artists who have worked and lived there include Joan Brassil, Sy Archer and David Fairbairn. A strong community living on land donated by art lovers Barbara and Nick Romalis in the 1970s, the Wedderburn artists’ “colony” continues to offer a refuge and resource almost unique in contemporary Australia.

In the bushfires of 1994 Cummings lost her studio, a blow which might have stopped a lesser person. But she soon built a bigger and better structure which served as both studio and home. The house and bushland around often apear in her work, as though the whole life-space is part of a continuous still-life.

Her large oils are notable for their heavily worked surfaces and colouring surprises. They offer secrets: spend enough time with them, and there is the reveal. The forms of the natural world appear through the scraping and marks on her surfaces. Her palettes seem tasty. Some, especially those reflecting the bushland around Wedderburn, are full of delicious soft pales and shadowy greens and browns. Others, in remote and outback places, are bright and hot, like a hit of chili and vinegar.

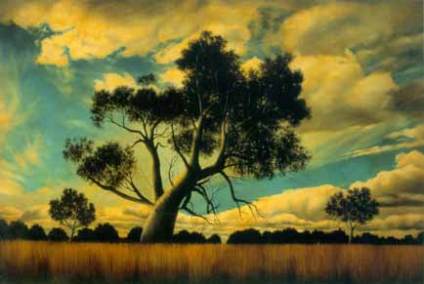

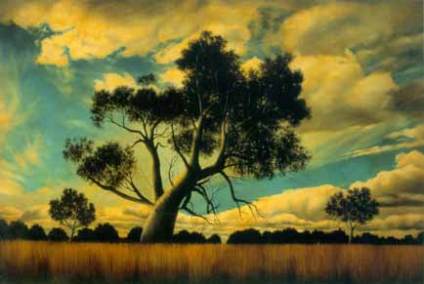

She isn’t immediate, or obvious. Comparing her visual impact with another little known but successful Australian landscape painter, Jason Benjamin, we see two aspects of the Australian heritage.

Jason Benjamin. This is Love. Oil, 434 x 291. www. Artistsandart.org

Benjamin works on a vast scale with immediately recognisable subjects, in a style securely located in European classicism (albeit with a strange surrealist quality). Cummings, on the other hand, hovers between the gestural demands of post-war European modernism and the meditative mysteries of the Australian vision imprinted with an Asian sensibility. There is Ian Fairweather in her slippery calligraphic marks, and Fred Williams in her itchy surfaces.

Ian Fairweather. Outside the Walls of Peking, 1935. Oil and pencil on board, 49 x 57 cm. Private collection, Perth.

Cummings has long been represented by King Street Galleries, now in William Street Sydney. She feels strong loyalty to the gallery, which has supported her work with well-mounted shows for decades (personal communication, February 2012). She has exhibited in some competitions and group shows, but most of her professional output has been sold through the gallery. Current listings at King Street have some of her recent works available, for instance Sir John Gorge Mornington, 2013, oil on canvas, 135 x 150; $48,000. The recent oils are quiet reflections on landscapes visited in the past. A beautifully delicate work, The Pink Outcrop, 213, 105 x 130, presents a lyrical pastel shaded landscape, tender and responsive. It sold for $35,000.

Photograph: King Street Galleries.

Her works from the middle 2000s show a strong sense of line and composition. Studio in the Bush (2006), 115 c 130, is a striking work based on her perception of the context of her life-space at Wedderburn. Journey Through the Studio (2004), 150 x 300, likewise offers a stunning meditation on the process of inhabiting the artist’s world, with its red and orange cadmium hues, the outline painting of a dog in the foreground, and the heavy dark wood-stove at the lower right. A strangely disturbing painting, it repays long scrutiny and engagement.

Journey Through the Studio (2004), 150 x 300. Photograph: King Street Gallery

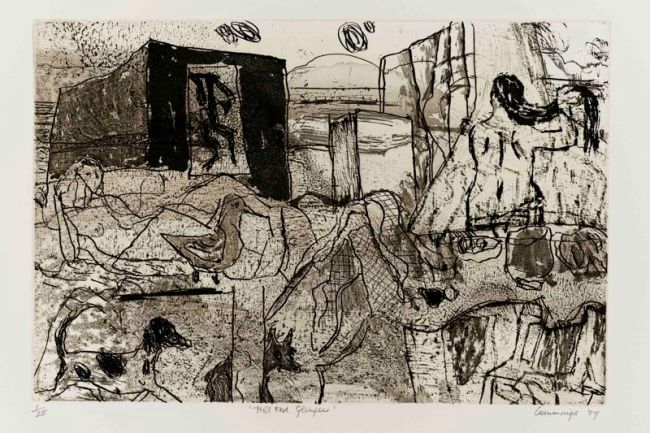

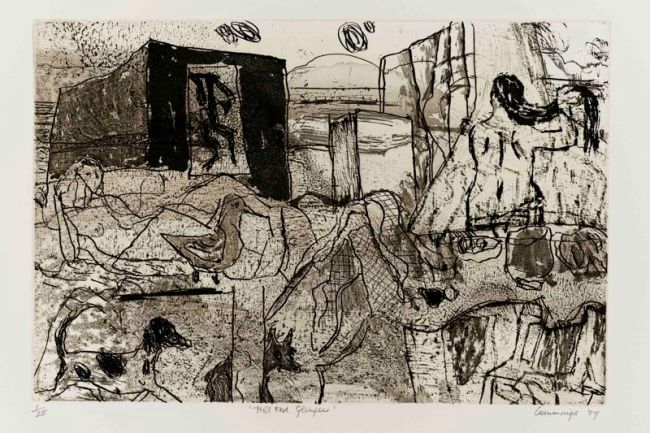

Cummings also works in prints and etchings. Her 2009 Hill End Glimpses is an artful tracery with several images seemingly hidden in the surface busyness. A woman stands, washing her hair. Two dogs trot along in the foreground. A large bird perches on a fence. Another woman lies reclining, perhaps in her sleeping bag. The square dark building with its enigmatic figure at the opening could be anything: a shed, or a house, or a storeroom. These are the painters, on their plein air excursion, taking the measure of the town of Hill End, made famous by the paintings of Russell Drysdale, John Olsen and others (see Australian Government, Hill End painters, n.d).

Hill End Glimpses. 2009. Etching, set of 25. Image: King Street Gallery.

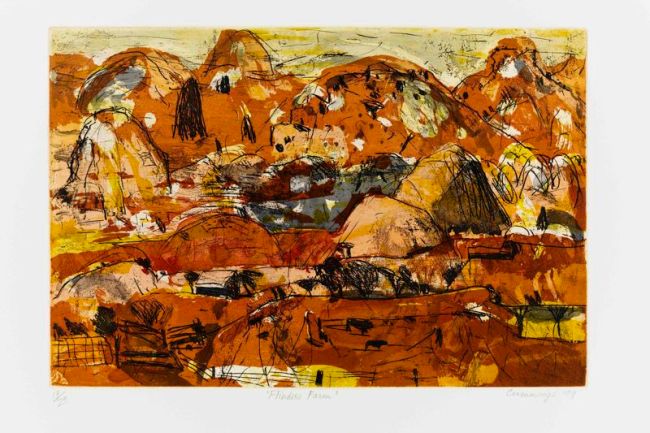

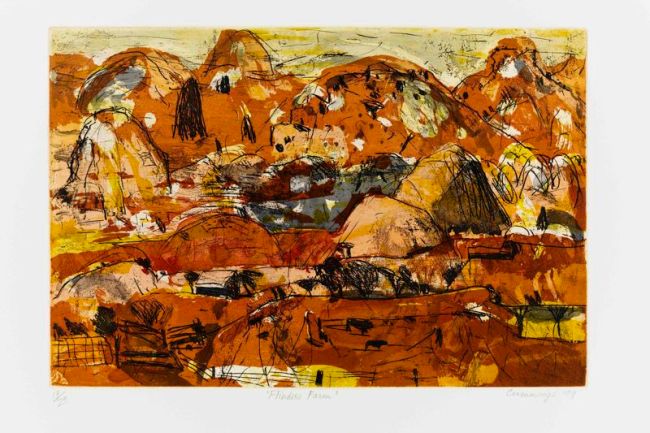

Arkaroola Landscape (coloured etching, 2005) uses a limited, traditional desert yellow to great effect. This remarkable piece was not hung in the Wynne Prize to which it was submitted that year, but towered over the other works in the Salon des Réfusés (McDonald 2012). Flinder’s Farm depicts the overwhelming quality of the semi-desert landscape and the futility of human efforts to farm there.

Flinder’s Farm. Coloured Etching 2009. Photograph: King Street Galleries

She speaks more about her etching and print-making in an interview, during a residency at COFA and work with Cicada Press (Butler, 2012).

She is always seeking new inspiration. Recently she has spent periods in India, working with children in a remote village, offering informal art training. She seems to accept no limitations: age, physical health, the effects of arthritis, the death of her close friends – she dwells in an intensely felt but manageable world, living through her own time and in her own places, which you can share through her art, if you so choose. What a privilege that is.

Real Still Life in the Studio. Photograph: Annette Hamilton 2012.

References

Australian Government. Australian Stories. Hill End painters – Donald Friend, Russell Drysdale, John Olsen, Margaret Olley and their legacy.

http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/hill-end-painters

[Accessed 22nd February 2014].

Butler, Angela. Interview: Elisabeth Cummings. November 27, 2012.

http://cicadapress.wordpress.com/2012/11/27/interview-elisabeth-cummings/

Champion, Stephanie. Pushing the boundaries with Elisabeth Cummings. http://www.bluebanksia.com/artworkshop-reviews/168-review-elisabeth-cummings.html) [Accessed 22nd February 2014).

Frost, Andrew. Elisabeth Cummings: The Invisible Woman of Australian Art. Art Collector. Issue 22, October-December 2002.

http://www.artcollector.net.au/ElisabethCummingsTheInvisibleWomanofAustralianArt. [Accessed 20 February 2014].

McDonald, John. Elizabeth Cummings. Art Essays, January 21 2012.

http://johnmcdonald.net.au/2012/elisabeth-cummings/#sthash.14IbTk1z.dpuf [Accessed 22 February 2014].

Meachem, Steve. Landscapes and private views. Sydney Morning Herald, January 4, 2012. http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/landscapes-and-private-views-20120104-1pl1i.html

[Accessed 22nd February 2014).

Pinson, Peter. Peter Pinson Interviews Elisabeth Cummings. Wedderburn, February 2013. http://www.cultconv.com/Conversations/Cummings_Elisabeth/HTML5/testimonybrowser.html [Accessed 21st February 2014].