ISAAC JULIEN: PLAYTIME

Roslyn Oxley9, Soudan Lane, Paddington, Sydney.

15th March – 12th April 2014

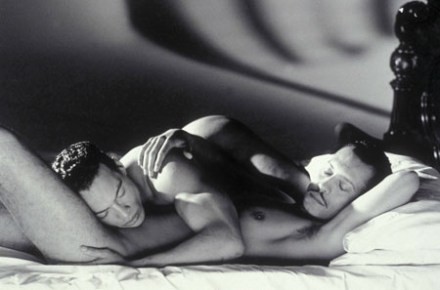

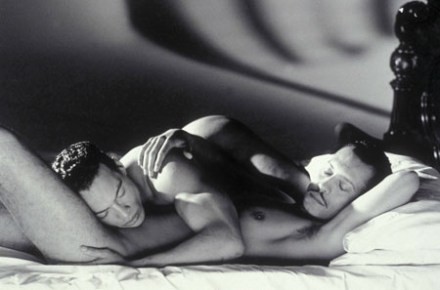

Isaac Julien: Publicity Still

Tucked away at the base of a majestic sandstone wall in Paddington, Roslyn Oxley’s gallery is a long-standing attraction for Sydney art-lovers, reputed for discernment without pretension. Established in 1982 and showing many rising stars, the gallery has moved to an exhibition program largely focussed on Asia-Pacific art, especially new arts of Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Prominent among the gallery’s represented artists are Hany Armanious and Michael Parekowhai (who represented Australia and New Zealand at the Venice Biennale in 2011) as well as Patricia Piccinini, Bill Henson and Tracy Moffatt.

This regional focus goes alongside a commitment to internationalisation. Artists such as Pierre et Gilles (1995), Robert Mapplethorpe (1996, 1997, 2000), Young British Artists Group Show (1996) and Moriko Mori (1997) led this trend in the 1990s, followed by Tracey Emin (2004) and Yayoi Kusama (five shows in the 2000s, most recently in 2012).

The recent installation by British film/video artist Isaac Julien continues it. However, Julien is not just an artist from another place, but an artist whose entire oeuvre has been concerned with the crossing of spaces, boundaries, identities and cultural forms, while exploring the relation between aesthetics and politics.

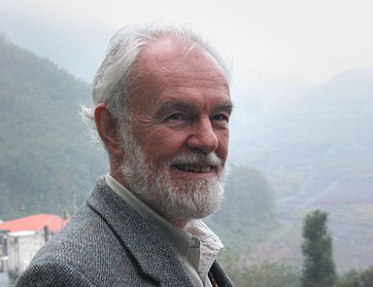

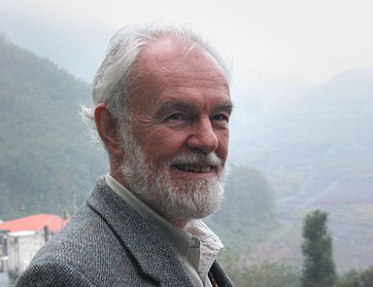

Isaac Julien, King’s Cross, Sydney, March 2014. (Photograph: Annette Hamilton)

Isaac Julien, King’s Cross, Sydney, March 2014. (Photograph: Annette Hamilton)

Born in London in 1960, of French Caribbean immigrant background, Julien embodies a bold transnationalism in life and work. Educated at Central St Martin’s School of Art with a BA in Fine Art Film, he went on to postgraduate study in audio-visual art in Brussels. Film, audio and photography in themed installations have become his signature mode, although the traverse to the present has been idiosyncratic at times. His art is well-known in film/video/politics circles, and he was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2001.

He began his work presenting intellectually engaged exercises in pop-cultural analysis which sustained the dynamism and sexy vitality of the era. Drama-documentary Looking for Langston (1989) gained a cult following with its exploration of Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance.

His next major film was Young Soul Rebels, which won the Semaine de la critique prize for best film at the Cannes Film Festival.

Movie Poster

Julien’s work crosses the lines between film, dance, photography, music, theatre, painting and sculpture. He creates powerful visual narratives which draw on elements of these varied disciplines. His earlier art films such as Three (1996-9), Vagabondia (2000) and Paradise Omeros (2002) explore issues in race, class and sexuality, sustaining within his video-art strong allegoric narrative elements. The same elements guided his exploration of mythic images of the cowboy in the context of gay culture and the West, in The Long Road to Mazatlan (1999). Restaging scenes from films by Martin Scorsese, Andy Warhol and David Hockney, he created a three-screen video installation mixing documentary with fiction, starring the Venezualan dancer and choreographer Javier de Frutos (see published conversation with B. Ruby Rich, 2002).

Few viewers of his recent projects would guess that another of his major works was a documentation of US Blaxploitation movies of the 1970s. BaadAssss Cinema: a Bold Look at ‘70s Blaxploitation Films was released in 2003 by the New Video Group Inc studio, an independent film channel. It included interviews with Quentin Tarantino, Pam Grier and other actors and filmworkers of that era, and artfully intercut clips and segments from some of the famous films of the time. The DVD of the film is still commercially available.

The same year he showed an art-film version of this project in a lush multi-screen projection Baltimore, which added a sci-fi twist to the blaxploitation conventions. Shot on 16 mm film, transferred to DVD and projected onto three big screens, the piece featured Melvin Van Peebles, director of the seminal film Sweet Sweetback’s BaadAssss Song (1971), in a tribute to black urban cinema. Street scenes of a ghetto neighbourhood are presented with a soundtrack including fragments of dialogue from Sweetback, while the real Van Peebles and a Foxy Brown-looking black woman walk through city streets. They arrive at institutions such as the Walters Museum, where they view Renaissance art. They walk through the hallways of various storehouses of artifacts and social styles creating a metaphorical journey through representations of temporal experience in the city. In a central passage of the show, Van Peebles confronts black heroes from the wax museum including Martin Luther King Jr and Billie Holliday (and himself) positioned in a painting gallery full of historical paintings. The film captures both a nostalgic sense of the vitality of black urban life, a perceptual funk scene, alongside a curious conversation between fantasies in historical space and time (Reid, 2004).

Murray (2004, p. 92) comments that Baltimore is “a continuation of Julien’s cinematic engagement with the contemporary exigencies of art history and the importance of the museum as a battleground for cultural legitimacy”. Technically, Murray also identifies one of the distinguishing features of Julien’s work, a visually intoxicating quality produced by the sense of “floating” as the camera moves through spaces creating layers of impressions, clusters of conceptual relativities. His use of multiple screens creates the viewer as individual editor of the text, so the chain of meaning is constructed from the flow of images.

Three films in the mid 2000s offered reflections on journeying across continents and cultures. These included True North in 2004 and Fantôme Afrique in 2005. A third, Small Boats, made up a trilogy which was screened in various venues such as Metro Pictures gallery in Chelsea. These films work from “real” backstories, and then elaborate on the themes raised through the split-screen camera technique. True North concerns the African-American explorer Matthew Henson who was the first man to reach the North Pole, although the white Robert Peary has always been credited with the achievement. Filmed in Iceland and Northern Sweden, the imagery grew progressively frozen and the icy wastes enfolded the narrative. Fantôme Afrique was filmed in Burkino Faso, the heart of the film industry in Africa, mostly taking place in the searing golden light of the desert. Small Boats links dance and film, shown in a single stage-wide screen. The three were shown as a trilogy at BAM in 2007, and an excellent interview with Martina Kudlacek illuminates much about his thinking and techniques (Kudlacek with Julien, 2007). To a degree, this phase of Julien’s work can be labelled “post-colonial”, although he distances himself from association with the label, while acknowledging the deep theoretical engagement which characterises his approach.

In 2008 he completed a film which surprised his fans and dismayed many critics. Titled Derek it offered an homage to noted British film-maker Derek Jarman, who had died in 1994. Critics commented on the extent to which this film lacked the stylistic elegance and subtlety evident in his earlier works. The film was seen as a conventional hagiographic documentary. Actor Tilda Swinton was a close friend of Jarman’s and hers is the dominant voice in the film, which seems to be a didactic exploration of the position of the gay filmmaker in contemporary society.

http://www.zimbio.com Sundance Portrait Session

Roger Cook (2008) offered a very negative commentary on the film’s political position, describing it as suffused with an “atmosphere of defensive ressentiment” (p. 38). Its “imperious political rhetoric” especially offended him, and his published critique in Art Monthly includes a particularly vicious unattributed quote about Julien himself: “It’s a spoilt bloke making spoilt films for spoilt people” (ibid). Nonetheless this piece does raise questions about the inextricability of politics and aesthetics (following Rancière) and suggests comparisons with Pasolini.

Julien moved from engagement with a single-screen cinema technology to the diverse potentials of multi-channel video installation (see Wu, Gough and Wall, 2012. His most striking exploration of this form is in his work Ten Thousand Waves (2010), a 55 minute installation designed to be viewed on nine double-sided screens, allowing eighteen different views of the installation. The audience can move around and view from any vantage point. The work moves between China’s ancient past and present, exploring the movement of people across countries and continents, engaged in permanently unfinished journeys. Its primary inspiration came from the Morecambe Bay tragedy of 2004 in Britain, when 20 Chinese cockle-pickers drowned on a flooded sandbank in northwest England. Maggie Cheung, famed Chinese actor, portrays the Chinese goddess Mazu from Fujian Province, the home province of the cockle-pickers. The film recounts the story of 16th century fishermen imperilled at sea. In a reenactment of classic 1930s film The Goddess, actress Zhao Xiaoshi plays the sea goddess who leads them to safety. The film is staged on the streets of modern and old Shanghai and uses music and sounds that fuse Eastern and Western traditions, with contributions from London-based musician Jah Wobble and the Chinese Dub Orchestra. The film took four years to research and create, and has been widely screened and praised around the world (MOMA publicity for installation, November 2013 – February 2-14).

Maggie Cheung in Ten Thousand Waves: publicity still

PLAYTIME

The project bears the same title as Jacques Tati’s 1967 film which offered a lightly constructed expression of dismay at the wreckage caused by modern capitalism (below, left: still from Tati’s Playtime)

PLAYTIME is a much more serious look at the same theme and is by far the most direct and articulate exploration of contemporary politics Julien has attempted. Although comments on the film frequently refer to it as exploring current debates on the relationship between capital and the art world, this theme is only one element in the piece. PLAYTIME and KAPITAL are shown simultaneously on endlessly looping screens in different but adjacent spaces. It is possible to move between them at any time, an illuminating viewing strategy. PLAYTIME consists of three elements, or chapters, set in three different cities defined by their relation to Capital: London, in the wake of financial deregulation; Reyjkjavik, where the 2008 crisis began, and Dubai, home of one of the world’s major financial markets. The main characters are played by actors enacting roles of The Collector, The Auctioneer, the Housekeeper and the Reporter, played by actors whose scripts are based on interviews between Julien and people affected by the financial crisis of 2007/8.

KAPITAL, viewed in a dark room with just two chairs side by side and two sets of headphones, offers a documentary-style film of a real panel interview intercut with a variety of scenes reflecting the comments in the panel discussion. David Harvey, author of The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism (2010), sits on the stage with Julien at the Hayward Gallery in London, along with an audience of critics theorists and curators.

David Harvey, from http://www.wideopenschool.com/class/Choreographing%20Capital

What occurs is a reprise of a 1960s Marxist discussion, somehow dislocated by the inability of the classic theoretical apparatus to accommodate the bizarre nature of contemporary global capitalism. This is the terrain Julien wants to take us through, but it is an uncertain journey. Entering debates so ethically charged and politically problematic is a dangerous manoeuvre. In his earlier works, which could be interpreted as aesthetic ventures into post-colonial worlds, viewers would not be disturbed from their ideological comfort zones. PLAYTIME and KAPITAL demand a different awareness and cannot be shoeboxed in the same way. Julien is talking about late global capitalism and the operations of the art market as an element in the transnational economy, run by dodgy financiers, fast-talking auctioneers and vaguely stupid collectors, where art fetches stratospheric prices and finishes up being dusted on the walls of luxury high-rise apartments in Dubai where nobody lives. Of course not everybody is going to like it.

Richard Woodward, in New York’s Collector Daily (December 4 2013) doesn’t, and doesn’t pull his punches.

It takes chutzpah for an artist to satirize the art market while fully benefiting from its largesse. Isaac Julien’s show is full of this double-talk. He is apparently upset at the gulf between rich and poor but views clueless collectors with disdain unless, of course, they happen to be shopping for one of his pieces … the artist manages to exhibit many of the hypocritical values his work wants us to abhor.

The work in PLAYTIME is complex and interweaves thematic elements in unexpected ways. It begins with a vast empty office-space in London. Two men walk about in random patterns, speaking the kind of financial-speak we have come to expect in contemporary discourse. In fact, some of their speech comes directly from David Harvey in the KAPITAL section of the installation. The city is spread out below them: the idea of Distinction depends on the maintenance of Greed. The Boss (played by British actor Colin Salmon) speaks of his need to employ only the top PhD graduates from Universities such as Harvard and Yale. With them he can keep the wheels turning. He explains hedge funds in bizarre terms, using an analogy with men’s underpants. In several strangely beautiful scenes we see a vast airconditioned warehouse full of computers, which is all you can actually see of capitalism: the lights blinking on and off as markers of the market. At the end of the segment the Boss walks about playing the trumpet, perhaps sobbing.

In the Iceland segment, the landscape occupies the entire screen, with plumes of smoke rising and hovering over the water. The central figure is a man who lost his self-designed ultra-modern home in the financial crash. He seems entirely overwhelmed by an irresolvable tragedy, expressed physically through his tortured physicality and desperate expression. How is the v iewer to respond? At first the viewer seems invited to identify with his pain. But soon one begins to ask, is it really such a terrible tragedy that a once-wealthy man lost his dream home? Isn’t his anguish and distress absurdly OTT? Why should people devote such passion to the building of “Their House”? What made it possible for him in the first place to acquire the capital which would allow him to engage in such a project? The vast empty premises of the Landsbankinn – one of the first banks to collapse – seems somehow appropriate to the icy wastes beyond.

iewer to respond? At first the viewer seems invited to identify with his pain. But soon one begins to ask, is it really such a terrible tragedy that a once-wealthy man lost his dream home? Isn’t his anguish and distress absurdly OTT? Why should people devote such passion to the building of “Their House”? What made it possible for him in the first place to acquire the capital which would allow him to engage in such a project? The vast empty premises of the Landsbankinn – one of the first banks to collapse – seems somehow appropriate to the icy wastes beyond.

The next London segment verges on satire. Actor James Franco plays a stereotypical art advisor extolling the value of contemporary art as a perfect investment for the diversification of a portfolio. As he walks up the stairs in a blank white-painted building he calls out numbers: 95, 100, 110, and for a moment you wonder what these figures refer to – but of course, they are millions, which is what the wealthy elites are now pay ing for art. At auctions the investors have advisers and agents on the phone, pushing prices up to astronomical levels supported by the insanity of the global economy. They can bid for and buy art from anywhere in the world, and they do: they come from Russia, from China, from Brazil. We meet the Auctioneer, in this case playing himself, Simon de Pury. He becomes anxious and excited before each major auction, eating an apple for luck. One “painting” which consisted of a written text on a wall sold for 1.2 million, a super-modest price compared with the 42 million paid for a Roy Lichtenstein in 2011. Art and antiques became part of the equipage of the wealthy class in the post-crisis mistrust of esoteric financial instruments. The Global Financial Crisis helped the art market beyond anybody’s expectations. During the GFC only 50% of items offered for sale were sold: now it is nearer 90%, springing back after the huge Christie’s auction in Paris in March 2009. Chinese star Maggie Cheung, who appears in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves, plays the role of an eager interviewer. In reality, the two never were together and each segment was filmed separately and intercut artfully.

ing for art. At auctions the investors have advisers and agents on the phone, pushing prices up to astronomical levels supported by the insanity of the global economy. They can bid for and buy art from anywhere in the world, and they do: they come from Russia, from China, from Brazil. We meet the Auctioneer, in this case playing himself, Simon de Pury. He becomes anxious and excited before each major auction, eating an apple for luck. One “painting” which consisted of a written text on a wall sold for 1.2 million, a super-modest price compared with the 42 million paid for a Roy Lichtenstein in 2011. Art and antiques became part of the equipage of the wealthy class in the post-crisis mistrust of esoteric financial instruments. The Global Financial Crisis helped the art market beyond anybody’s expectations. During the GFC only 50% of items offered for sale were sold: now it is nearer 90%, springing back after the huge Christie’s auction in Paris in March 2009. Chinese star Maggie Cheung, who appears in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves, plays the role of an eager interviewer. In reality, the two never were together and each segment was filmed separately and intercut artfully.

Meanwhile, in Dubai, the financial capital of the Middle East, a beautiful but sad housekeeper in a black and white uniform walks sadly back and forward through an empty luxury apartment.

Mercedes Cabral as The Housekeeper: publicity still

Played with a sensitive but unemotional demeanour by Mercedes Cabral, Filipina actor best known for playing in art house and independent films, this sector seems oddly out of adjustment with those preceding it. At times we seem to be overhearing an ethnographic interview, as she explains that she had to pay an agency 150,000 pesos to get the job in the first place. She needs the money to support her family at home. The inhabitants of the vast elegant apartment with its art pieces never appear. She dusts, and gazes. Long periods of silence accompany empty visuals of the vast city outlook with its lights and vehicles stranded in the midst of an empty sand desert, where she stands staring into the distance in the closing scene.

How can we understand contemporary capitalism: is it the same as it was, or are we seeing something altogether different? Analysis of something so invisible and intangible seems an absurd venture. Images of riots, computers and banks of neon numbers as well as talking heads and actors who may or may not be playing themselves make it hard for most viewers, who may not be able to take in the theoretical issues being debated here, many of which go back to bitter political fights of the 1960s. But is a video installation the right place to be asking these questions? Or are there other questions lurking behind which we haven’t yet asked?

Some commentators appear bemused. Others, such as Searle (2014) pick up on the uncertainty produced by Julien’s method while appreciating its strengths.

There is brilliance and disappointment in Playtime. A hybrid of fiction and documentary, the film makes it difficult to know what is real. I wander between the screens, lost in Julien’s cinematic subterfuge, and that, I think, is the point.

Hybrids of documentary and fiction are common in literature, much less so in cinema, although re-enactment has become a common strategy in commercial television of recent times. Still, the breaking down of barriers between reality and imagination seems particularly challenging. For an art film-maker to be giving us a lesson in Marxist theory seems strange today although it was hardly unknown in the 1960s especially in the Latin American revolutionary context. For that lesson to be couched in the method of a hyper-developed media technology and elevated aesthetics is harder still to accommodate. It is hardly surprising If it proves almost impossible to say something which will be widely understood on a topic which is, for most people, entirely ungraspable. What is fascinating is the extent to which Julien is willing to push the boundaries even while maintaining a certain tongue-in-cheek distancing from them. Unlike Searle (ibid) I didn’t find any longeurs in this work but I would have liked to see a bit more speed and directness in the Dubai section which seemed to link only vaguely to the direction of the other elements.

In terms of strategy of presentation, the use of two separate linked spaces, both lit only by reflected light from the screens, separated the viewer’s intellectual and aesthetic engagement. At Roslyn Oxley9 the main viewing area featured a long wide bench, on the edge of which viewers had to perch. Or, in some cases, lie down. When there were more viewers, they had to crouch on the floor.

This was an odd viewing experience, emphasising a kind of static loneliness in the encounter with the work, unlike previous projects which required active mobility from the viewer in constructing imaginative connections. Its ability to connect with the intended audience is necessarily compromised by the peculiar position it opens for them. There is a quality of introspection which takes precedence over the usual sense of delerious enjoyment found in his work. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the great majority of consumers in the art market really do not want to discuss the urgent issues surrounding global capitalism, and Julien’s desire for them to reconsider does not make for a comfortable engagement. Notwithstanding such critiques, the film is undeniably provocative and very beautiful.

REFERENCES

Art iT 2013 Isaac Julien Part 1.

<http://www.art-it.asia/u/admin_ed_feature_e/n6fMcR3eJU52sQuiTPqF >[Accessed 3 April 2014).

Cook, Roger. 2008. Isaac Julien’s Derek. Art Monthly, April, p. 315.

Harvey, David. 2010. The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

Harvey, David. N.d. Reading Marx’s Capital with David Harvey. <http://davidharvey.org/reading-capital/> [Accessed 6 April 2014)

Julien, Isaac. 2008. The way I see it: artists tackle ten existential questions. New Statesman, June 16,Vol 137 p. 40.

Kudlacek Martina and Isaac Julien. 2007. Isaac Julien. BOMB No 101 (Fall pp. 72-79. [Accessed 26/03/2014]

Murray, Soraya. 2004. Isaac Julien: Baltimore. Journal of Contemporary African Art, Summer, 92-93.

MOMA. 2013. Isaac Julien: Ten Thousand Waves. The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium. MOMA, New York: Publicity Materials.

Reid, Calvin. 2004. Funk Renaissance. Art in America. March, p. 92-95.

Searle, Adrian. 2014. Playtime. London. The Guardian.

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jan/29/playtime-james-franco-power-money-isaac-julien-capital

[Accessed 4th April 2014]

Woodward, Richard. 2013. Isaac Julien PLAYTIME @ Metro Pictures. <http://collectordaily.com/isaac-julien-playtime-metro-pictures> [Accessed 4th April 2014)]

Wu, Ge, Phillip Gough and Caitlin de Berigny Wall. Multiple-channel video installation as a precursor to transmedia-based art. 2012. Technoetic Arts: a Journal of Speculative Research, Vol 10, 2/3, pp. 329-339.

On post-colonialism in Julien’s art: (Interview with ART iT)

ART iT: When you were starting out as an artist was post-colonial theory an inspiration for you, and did you actively use it in constructing your works?

IJ: Absolutely. I couldn’t have made my early films like Territories (1984) and Looking for Langston (1989) without it. Along with my peers I read Stuart Hall, Gayatri Spivak, Paul Gilroy, Richard Dyer and, of course, Homi Bhabha’s famous essay “The Other Question” (1983). Then in 1988 I was on the editorial board of Screen journal with the cultural art critic Kobena Mercer. But I wasn’t exclusively interested in post-colonial theory. I was also interested in film theory and psychoanalysis and a translation of those ideas across media. In 1995 it was really exciting to attend the “Frantz Fanon and Visual Representation” conference at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, which coincided with the making of my film Frantz Fanon: Black Skin White Mask (1996) in collaboration with Mark Nash, who was also an editor of Screen and a curator for documenta11. Steve McQueen made his first exhibition there and artists like Glenn Ligon and Lorna Simpson were also present in an exhibition that coincided with the conference, “Mirage: Enigmas of Race, Desire and Difference.” Retrospectively, you could see it as part of the formation of a conceptual Black arts movement – some might call it “post-Black” – in which there were these different nuances that developed in different practices.

But of course as an artist you evolve in different directions and engage with other discourses. In 1999 I made the film installation Long Road to Mazatlán, which was ostensibly about two cowboys in the American West and was nominated for the Turner Prize. It was a deliberately Warholian-type work and through it I think I was already challenging what I saw as the post-colonial paradigm. I purposely cast two white protagonists, one of whom was the choreographer and dancer Javier de Frutos, who collaborated with me on the project. Of course, they were queer, and there was this Warholian play with desire and the quotational Pop-art element, but I think I was already conscientiously trying to upend post-colonial expectations. Some of my friends saw the piece and told me, “Oh, that’s a bit odd for you to make, Isaac.” And I thought, “Well, that’s exactly my point!”

That said, I take it for granted that post-coloniality might be one of the themes in my work. It simply won’t be my sole theme of interest. Unfortunately, that’s not everybody’s point of view.

I forget where we were, 2015, oil on canvas, 63 x 138cm

I forget where we were, 2015, oil on canvas, 63 x 138cm

iewer to respond? At first the viewer seems invited to identify with his pain. But soon one begins to ask, is it really such a terrible tragedy that a once-wealthy man lost his dream home? Isn’t his anguish and distress absurdly OTT? Why should people devote such passion to the building of “Their House”? What made it possible for him in the first place to acquire the capital which would allow him to engage in such a project? The vast empty premises of the Landsbankinn – one of the first banks to collapse – seems somehow appropriate to the icy wastes beyond.

iewer to respond? At first the viewer seems invited to identify with his pain. But soon one begins to ask, is it really such a terrible tragedy that a once-wealthy man lost his dream home? Isn’t his anguish and distress absurdly OTT? Why should people devote such passion to the building of “Their House”? What made it possible for him in the first place to acquire the capital which would allow him to engage in such a project? The vast empty premises of the Landsbankinn – one of the first banks to collapse – seems somehow appropriate to the icy wastes beyond. ing for art. At auctions the investors have advisers and agents on the phone, pushing prices up to astronomical levels supported by the insanity of the global economy. They can bid for and buy art from anywhere in the world, and they do: they come from Russia, from China, from Brazil. We meet the Auctioneer, in this case playing himself, Simon de Pury. He becomes anxious and excited before each major auction, eating an apple for luck. One “painting” which consisted of a written text on a wall sold for 1.2 million, a super-modest price compared with the 42 million paid for a Roy Lichtenstein in 2011. Art and antiques became part of the equipage of the wealthy class in the post-crisis mistrust of esoteric financial instruments. The Global Financial Crisis helped the art market beyond anybody’s expectations. During the GFC only 50% of items offered for sale were sold: now it is nearer 90%, springing back after the huge Christie’s auction in Paris in March 2009. Chinese star Maggie Cheung, who appears in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves, plays the role of an eager interviewer. In reality, the two never were together and each segment was filmed separately and intercut artfully.

ing for art. At auctions the investors have advisers and agents on the phone, pushing prices up to astronomical levels supported by the insanity of the global economy. They can bid for and buy art from anywhere in the world, and they do: they come from Russia, from China, from Brazil. We meet the Auctioneer, in this case playing himself, Simon de Pury. He becomes anxious and excited before each major auction, eating an apple for luck. One “painting” which consisted of a written text on a wall sold for 1.2 million, a super-modest price compared with the 42 million paid for a Roy Lichtenstein in 2011. Art and antiques became part of the equipage of the wealthy class in the post-crisis mistrust of esoteric financial instruments. The Global Financial Crisis helped the art market beyond anybody’s expectations. During the GFC only 50% of items offered for sale were sold: now it is nearer 90%, springing back after the huge Christie’s auction in Paris in March 2009. Chinese star Maggie Cheung, who appears in Julien’s Ten Thousand Waves, plays the role of an eager interviewer. In reality, the two never were together and each segment was filmed separately and intercut artfully.