CHRISTIAN BOLTANSKI: CHANCE

Christian Boltanski’s art patrols the borders of an existential philosophy exploring randomness, memory and death. He works through large-scale installations which have been seen at many prestigious art events around the world, including at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, Künstalle Wien, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and many others. The installation Chance, consisting of three elements, Wheel of Fortune, Last News from Humans and Be New (2011) was presented at the French Pavilion at the Viennale, and later shown in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and in Brazil before its presentation at Carriageworks as part of the Sydney Festival (Carriageworks 2014).

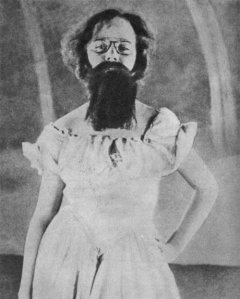

Boltanski left formal education at the age of 12, seemingly suffering from something like autism. Self-taught, he began painting in 1958 when he was fourteen years old. He came to public attention in the late 1960s with a series of short avant-garde films and the publication of notebooks in which he reflected on his childhood. All of this work combined reality and fiction, offering doubtful evidence about his own and other people’s existence.[1] In the 1970s he turned to photography using objets trouvés as subjects. Then he began creating marionette-like figures from cardboard and scraps, transposed into large picture formats. Mysterious shapes of silhouettes in movement emerged (Fox 1998).

But the kind of work for which he is best known emerged in the mid 1980s when he began making installations from different materials and media. His installations rely on the ephemera and off-casts of human experience. He has used obituary photographs, lost property, and forms of memorialisation of unknown people. In one work he used portrait photographs of Jewish schoolchildren taken in Vienna in 1931 as a reminder of the mass murder of Jews by the Nazis. In another he filled rooms and corridors with items of worn clothing as a reminder of the clothing depots at concentration camps. Objects were used as testimony to human experience and suffering (Franzke, n.d.).

Contemporary trauma theory would suggest that he, like many other artists, was using his art to “work through” some specific elements in his personal biography.

Melvyn Bragg, in the video interview directed by Gerald Fox (1998) repeatedly attempts to return to the idea of a traumatic kernel at the centre of Boltanski’s art, something located in his own biography. He was born in Paris in 1944. The war in Europe was almost over by that time. The events of the war, the persecution of the Jews, the realities of the concentration and extermination camps, would have long ended by the time he became old enough to be aware of social and political matters. His work on themes related to extremity, memory, suffering and chance seems to have this origin but apart from brief comments in interviews it is difficult to be sure of “the facts”. Even the text often referred to as his “memoir” (Boltanski and Grenier 2009) is entitled “The Possible Life…” which leaves its basis open to interpretation.[2] Nevertheless something in the conditions of his childhood similarly influenced his brother, about whom he hardly ever speaks.[3]

His brother, Luc Boltanski, is an eminent Professor of Sociology in France’s most prestigious Insitute of social sciences, the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, in Paris, and is the leader of a new “pragmatic” school of French sociology, known for its political and moral framework. His work lies broadly in the field of biopolitics. In his book Distant Suffering: Morality, Media and Politics hedescribes a politics of pity based on the spectacle of suffering. Viewing by the fortunate who do not share the suffering of those they observe is the basis of this politics. Mass media in particular television has spread this mode of perception and public reaction to the rush of uncontrolled events in reality.

Victimhood provides a particular identity and the politics of pity demands that the observers find a way to urgently assist them. This is not a matter of formal justice: there can be no question of who is “at fault”, merely a recognition that those who suffer must be assisted. “The development of a politics of pity thus assumes two classes which are not unequal by reference to merit … but solely be reference to luck” (L. Boltanski, 1999: 5). It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the works of both brothers may arise from a common strand.

C. Boltanski likes to present himself as trangressive or even shocking. In the 1980s he spoke of the artist’s life as like a Hasidic tale or a Zen story. He claimed that artists are like saints who live in the desert on top of columns, but at the same time are crooks. He wants to make a moral work, speaking of universal things, life and death, being and not being. He claims he, and other artists, are like preachers, believing in their art and yet being somehow false. Works of art are like relics, he says, and the more you create, the more you disappear and so you are in a way invisible or dead. This article is extremely revealing regarding his philosophy at that period, with useful comments on the relation between his work and the Holocaust, especially on the large piece The Children of Dijon (Borger 1988/89, p. 24).

Impermanence, transience, and loss is reflected in the works themselves, which cannot be “collected” in any conventional sense. The vast installations are destroyed after exhibition. This highlights one of the most puzzling questions about artists like Boltanski. Their work is entirely conceptual. They do not “make” their art. All of their exhibits have to be constructed and managed by others. In what sense is the creator an “artist”? Can art be separated from the physical action of its creator? Does the contemporary, or perhaps it is post-modern, obsession with conceptual art and installation arise from an ethical insistence on the priority of idea over form and of collective effort above private individual labour?

There have been other, deeper, critiques of Boltanski’s oevre. For example some have questioned the ethics of his position. He seems to apply an almost complete lack of differentiation between individuals and types or groups of people. This is very evident in Chance.

The Polish newborns are located within a “space” – Poland – but out of time. They might have been born in the 2000s or for that matter in the 1940s. Their fates of course would be totally different, and this is the central point Boltanski is trying to make. His modes of representation do not distinguish between the origins and consequences of the operation of random fate. In another work, Les Archives: Detective (1987) he drew no distinction between victims or murderers. As Solomon-Godeau suggests, “it implies a bottom line equivalency from which ethical distinctions are banished. This means we are unable to cast judgment on those represented.” (2012: 8). A counter-argument could be offered: that there should be a basic equivalent respect for all individuals, regardless of their deeds. This seems a view quite consonant with much contemporary ethical philosophy, which undermines the traditional expectation of ethical judgments arising from collectively recognised justice and morality. It is a form of postmodern relativism in the field of ethics.

Other critics express disgust with Boltanski as one among many others whose fundamental preoccupation is with an empty euphoric-apocalyptic hysteria disguised as a form of politics. Charlesworth, for example, says:

But it’s everywhere — from Allora & Calzadilla’s United States of Self-loathing, to Mike Nelson’s anxious simulation of an alien Middle East, to Christian Boltanski’s crazed machine of speeding overpopulation — the nervous breakdown of a politics of crisis suffuses every pavilion. It’s like being in a room full of manic-depressives who haven’t had their meds, all sobbing and babbling. (Charlesworth 2012, p. 56)

While this is over-stating the case, there is nonetheless a certain force to this view, raising questions about the forms of political engagement possible for the contemporary artist.

“Chance” at Carriageworks

It is a warm humid day in Sydney. The sun streams down from a vivid blue sky.

Carriageworks offers an amazing visual space. Its vastness and clear panels of roofing create a mobile tableau of lights and darks. The walls have been preserved, or rather paused in their process of decay. Rust gathers along the chrome yellow girders, No L 64, high above the floor level, announces LOADING TO EXCEED 10 TONS. This girder, its depth and solidity, anchors one end of the building. Two smart-looking fellows are perched at tables, staring at computer screens. Cutlery gleams inside shiny tin cans. The napkins are made of brown heavy paper. Light illuminates brick-red pipes which support interior lights.

Boltanski’s gigantic work Wheel of Fortune is easily contained here. Sunlight illuminates the bright silver scaffolding, eight metres high, weighing twenty tons. Its intricate assembly creates a layered perspective through which the endless line of enlarged black and white images of newborn baby faces pass. They move at a steady pace, until a bell rings and the loop of grainy images comes to a halt, the camera capturing one child’s face which is displayed on a screen.

These are photos of newborn babies, taken from the birth announcements of Polish newspapers. They could be from any age, any place. Seeing them at the far end of the installation, they are now reversed. It makes no difference. The intent behind the display is simple: all people are the product of a chance moment, of the specific moment when their parents made love; had it been before then, or afterwards, each person would have been different. A technical and temporal flash creates us all in our apparent difference and uniqueness.

An employee has to be present at all times to make sure that the machinery governing the movement of images through the vast scaffolding is not interrupted by some mechanical failure. When after the first installation it proved too hot for the glue holding the screen of images together it was necessary to find skilled artisans with large machines able to sew the canvas materials on which the images were printed together (personal communication, staff member, February 2014).

At each end of the piece, the second element of the exhibit is located high above the heads of the viewers. Last News from Humans displays two digital tallies in real time showing births and deaths around the globe. The yellow/green shows the number of births, the red the number of deaths. Through the flashing lights we see how quickly lives are created and end.

It’s sobering to consider the discrepancy between the numbers being born and the numbers dying. At the time of my viewing, 176,000 were born and a mere 66,000 died – or had died at some specific time, although this was not well explained. My immediate thought: more people should die. I mention this to the young man overseeing the operation of the machinery. He seems shocked. We are supposed to think that fewer people should be born. There are deep existential and philosophical issues here.

To one side is the third part of the exhibit, Be New. This consists of three disparate photographic sequences, images of the Polish newborns intercut with images of deceased elderly Swiss people. The latter images came from another Boltanski installation. There are potentially 1.5 million combinations from the three segments. The viewer presses a button and produces a new human face. This is meant to remind us that we are all composites of our ancestors.

I get this exhibit, in a way I hadn’t expected. It is disturbing and beautiful at the same time. But it is also quite banal. It looks “lovely” in this space, but that’s largely due to the space itself. The aesthetic pleasure offered by the walls is stunning.

Cross-hatched concrete fills in corners; white brick is rubbed back and scrabbled over with dirt and rust. This is a real monument to generations past – to a lost way of life, a time when human labour alone created spaces like this with real human muscles, sweat, blood and optimism. The net of connections across the state of NSW depended on this place, without it there would have been no railways. I find this thought far more compelling than pondering Boltanski’s anonymous Polish babies.

His sensibility is that of old Europe. There is a place for that, and we should be reminded. But we are in the south, the humid air of the Pacific washes through the doors, the sun shines. There are definitely too many people in the world, and yes, chance seems to allocate some to here and some to there, a process which is truly “random”. It is true we would be different – a bit different – if our parents had carried out the reproductive act at a different moment. Would that matter? Larger, more urgent, questions seem occluded or disguised by this seemingly philosophical work. The focus on the individual – on the idea of being “somebody” – pushes the broader historical and political issues aside. Boltanski’s entire oeuvre has been obsessed with memory and the traumatic residues of twentieth century history. Questions of human existence explored through a post-Holocaust aesthetics may seem at one level to be an ethical stance, but where can it go from here? Boltanski’s installation is surprising and strangely beautiful, but it made me think far more about why we have no properly functioning railways any more, a question of huge political and ecological significance for the future of this beautiful land, which could provide the basis for a more relevant work of art. This calls for a form of ethical judgment which takes into account the broader role of art. As Nowak comments:

…judgment in general should be understood as intrinsic to the task of art criticism. I argue that judgment is under-theorized in contemporary visual art critical circles and that the ethical judgment of art is of particular importance. My position is something of a departure from dominant understandings of judgment in these circles, for since the end of modernism, judgment (of whatever type) has been widely held to be either outmoded or inappropriate. (Nowak, 2012, p. 8).

Work such as Boltanski’s pushes the viewer directly into a world where judgment is invoked and ethical perspectives are invited. For this we should be grateful, while recognising that there are historical and cultural factors requiring urgent consideration of the role and value of art today.

References

Boltanski, Christian with Catherine Grenier, 2009. The Possible Life of Christian Boltanski. 1st ed. US: MFA Publications.

Boltanski, Luc, 1999. Distant Suffering: Morality, Media and Politics. 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University press. First published as La Souffrance a Distance, 1993, Paris: Editions Metaille)

Boltanski, Luc with Chiapello (Ève), 2005. The New Spirit of Capitalism, London/New York, Verso.

Boltanksi, Luc. 2011. Une étude en noir. Tracés. Review des Sciences Humaines, 20, 2011. On Line 16 May 2013. http://traces.revues.org/5049. [Accessed 1st March 2014].

Borger, Irene and Christian Boltanski. 1988/1989. Interview. Bomb, 26, 22-27.

Charlesworth, J. J., 2012. Boltanski. Art Review, 56, 52.

Fox, Gerald (Dir). 1988. An Exploration of Art on Film. English, Pal, VHS.

Franzke, A. n.d. Christian Boltanski. Artist biography. Tate Modern.

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/christian-boltanski-2305

[Accessed 15 Feb 2014].

Nowak, Jolanta, 2012. Judgment, Justice and Art Criticism. Contemporary Aesthetics,10, 8.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail, 1998. Mourning or Melancholia: Christian Boltanski’s Missing House. Oxford Art Journal,21, 2, 20.

Catalogue Essays:

Christian Boltanksi, 1978. Reconstitution. Exhibition Catalogue, ed. A. Franzke and M. Schwarz, Karlsuhe, Bad. Kstver.

Christian Boltanksi, 1984. Exhibition Catalogue, Ed. B. Blistene, Paris, Pompidou,

Christian Boltanski: Lessons of Darkness, 1985. Exhibition Catalogue, Ed. L. Gumpert and M. J. Jacob; Chicago Ill: Museum of Contemporary Art.

Photographs: All photographs taken by Annette Hamilton at Carriageworks February 2014 unless otherwise credited.

[1] The casting of doubt in artistic works is highly characteristic of many forms of art in the late twentieth century, often with reference to the Holocaust and its aftermath. In literature an outstanding example is the long writing – novel, memoir, fantasy? – Austerlitz, by W. G. Sebald (2001). In Austerlitz, Sebald not only writes about somebody who might or might not exist telling the story of someone else who might or might not exist, he presents series of photographs which the reader is invited to take as visual evidence of the “truth” of his narrative, even though the source of the photographs is unacknowledged. This profound unsettling of the boundaries between “truth” and its representation is very evident in Boltanski’s work, as is clearly evident in his strange insistence on obscuring his own identity and taking on guises such as “the Preacher”.

[2] This tendency to self-mystification, or at least to obscuring elements of biography, contrasts with the usual pattern of self-disclosure common among fiction writers and poets. The insistence by “the public” on knowing everything about their artistic heroes does not recognise the legitimacy of such distinctions.

[3] His self-construction wavers but he often claims the conditions of Nazi occupation in Paris as a source of his artistic themes. In conversation with David Walsh, owner of Museum of Contemporary art in Tasmania, he spoke of himself as “a sort of survivor”. He describes how his Catholic mother hid his Jewish father under the floorboards although this feels as if it could be an apocryphal story. See http://www.au.timeout.com/sydney/art/features/12957/christian-boltanski-on-chance